Action at Once Rational and Ardent

- avitalbalwit

- Dec 11, 2024

- 8 min read

“a nature altogether ardent, theoretic, and intellectually consequent..."

- Middlemarch, Chapter 3

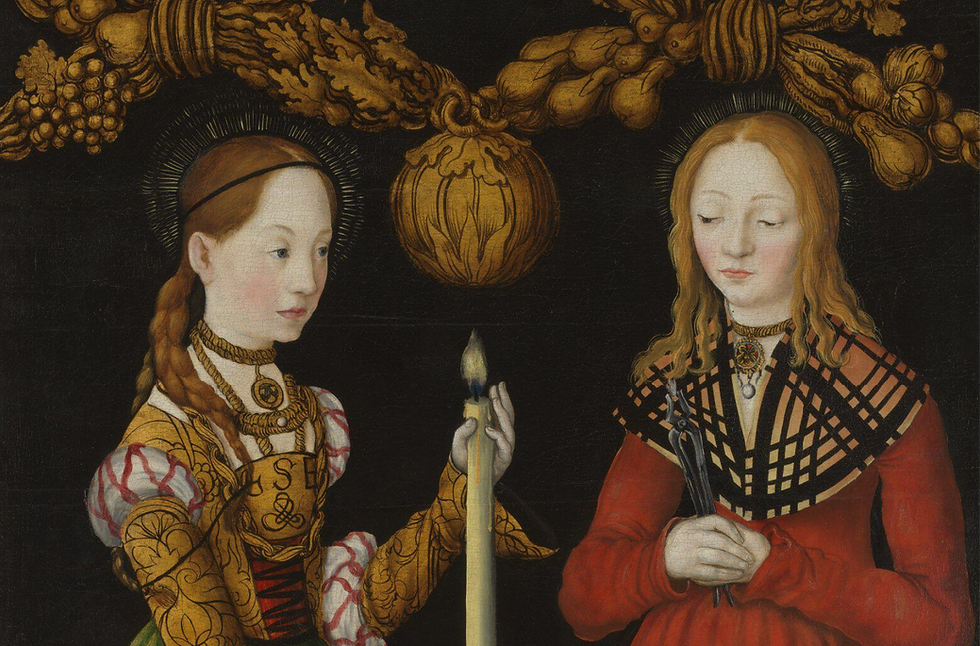

Detail from Lucas Cranach the Elder: Saints Genevieve and Apollonia from The St Catherine Altarpiece: Reverses of Shutters, 1506

Consider these people:

The young democratic socialist who spends Thursday evenings at their YDSA meeting, who donates spare change to a mutual aid fund, who spends their Saturday knocking doors for Sanders, who reads Jacobin and N+1, who studies Political Philosophy or African Studies or Sociology.

My grandma who went to Church each Sunday, who never swore, who didn’t drink, who prayed before every meal, who spent months volunteering to train teachers in Namibia, who worked to translate the bible into tribal languages, who donated to whatever cause her Church directed her to, who took people into her home when they needed it, who invited strays to her holiday dinners.

The environmentalist who carries their reusable bags and water bottles, carefully recycles and composts, is vegetarian, donates to the Sierra Club or Sunrise, who is reading “This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate” or “The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming”; who avoids flying when they can or buys offsets, who votes based on climate.

The effective altruist who tries to choose their donations and career based on “impact, neglectedness, and tractability” and who works on something like AI safety, biosecurity, farm animal welfare, global health, preventing nuclear war, who donates to Givewell, is vegan, listens to the 80k podcast, is reading “The Precipice” or “What We Owe the Future” or “Doing Good Better.”

These projects look different. One could conclude there are multiple ways to be good, or that most of these are wrong (or, more likely, all of them are wrong). So why laud them?

Because the questions they’re trying to answer seem so deeply important: What matters? What does it mean to be good? How should I act so as to be good?

Their ways of living in response to these questions display three laudable traits:

Other orientation

Consistency

Intensity

My interest in people like this was reignited by reading what has become my favorite book: Middlemarch. Middlemarch is many things: a subtle depiction of social interactions; a perfect, self contained world that is both a snapshot in time and surprisingly familiar; and it is one of the best explorations of how to be good in our mundane lives. The main character, a young, soulful and earnest woman named Dorothea, spends the book trying to understand what it means to be good and then to do it. She is searching for an overarching set of principles to guide her life. Given her Zeitgeist, she approaches this primarily through religion but this merely provides the language. The results are transferable.

Other orientation

"I should like to make life beautiful. I mean everybody's life..."

Dorothea Brooke, Chapter 1

I am moved by those who sacrifice for others, or even simply those who extend their efforts beyond self-interest. Yes, political and social expression can also make us feel good and can be signaling, but I think it almost always reflects some amount of genuine concern for others. Consider people engaged in projects like preventing abortions or stopping climate change; Given the scale and the way the costs of these issues shake out, the effects will fall primarily on others, not themselves. Yet they spend their weekends and spare resources on these causes rather than purely personal pursuits. The pull of self interest is so strong and so constant that I respect those who can see and act past it.

Dorothea asks, "What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult for each other?" (Chapter 72). Well, there are some other things to live for: to be happy, to create and experience beauty, because we find ourselves already situated in the living. But it does seem that a complete life should involve some amount of making life less difficult for each other. We are social animals. And I believe we are also moral ones. By this I mean we have broadly shared intuitions about right and wrong that cross times and cultures. (People spend too much time focusing on the fringe cases where these intuitions differ — I am always struck by the broad core of where they are the same. So many cultures value honesty, loyalty, love, compassion, and so on. Basically all have the same revulsion towards those who cause needless suffering.)

Some object to this view. You’ll meet the rare committed Randian who thinks that altruism leads you astray; that the best guide of what to do is what you want to do. This prevents you from wandering off into misguided theoretical projects. I would still say that if “making life less difficult” is no part of what you want to do, then you are imbalanced, unwell, immature, not finished, etc. I don’t mind if the goodness is something you want or enjoy — all the better I’d say. But you should do it regardless, perhaps because you want it, perhaps even if you don’t.

Dorothea says: "I try not to have desires merely for myself, because they may not be good for others, and I have too much already." (Chapter 3). For essentially everyone who reads this, we do have “too much” in the sense that our needs are beyond met. Many of us live in conditions of historically abnormal abundance. Dorothea is extreme here — I agree with her last phrase, but perhaps not her first two. It is likely alright, or at least certainly forgivable, to have the occasional desire merely for yourself, even while having too much. But there is something appropriate about recognizing the abundance and for it to encourage one to turn outwards, towards those with less. Your security should make you bolder. You should take risks to improve the world that others cannot afford, you should share when you can.

Consistency

"Her mind was theoretic, and yearned by its nature after some lofty conception of the world which might frankly include the parish of Tipton and her own rule of conduct there... The thing which seemed to her best, she wanted to justify by the completest knowledge; and not to live in a pretended admission of rules which were never acted on."

- Chapter 3

Consistency involves drawing a thread from one part of your life through to another, making sure that when you consider your actions as a whole that they aren’t working at cross purposes, that they all align with your values and goals.

When someone claims to be pro-life, and is against abortion but in favor of the death penalty, their opponents frequently call them inconsistent. These opponents might still disagree with someone who is against both abortion and the death penalty, but at least they would have to admit such a position is consistent.

Consistency begins as an intellectual practice — the rigorous extension of our beliefs and principles across all domains of life, recognizing that if something is true or right in one context, it has implications for others. But it becomes moral when we confront the uneven costs of living up to these implications. Some domains demand more sacrifice than others, and consistency requires us to overcome the temptation to apply our values selectively. My sister exemplifies this: she loved eating meat, but she gradually became compelled by arguments for animal welfare. Rather than compartmentalize this belief or apply it only where convenient, she chose to become vegan despite the inconvenience — aligning her actions with her growing moral understanding.

Consistency is attractive because it shows that someone has contemplated their life as a whole and aligned it, which shows self reflection and intellectual seriousness, or, if this was done unconsciously and intuitively, shows that the person has such a stable and well integrated self that their life is naturally consistent.

Our lives are often complex enough that running an additional computation of “what is the moral effect of this” or “is this act consistent with my philosophy or principles” is somewhere between impossible and impractical. One either needs to reflect at certain, time bounded points or have simple principles, easy to remember and apply.

That’s why something like virtue ethics appeals: try to become a certain kind of person, and then your character will guide you through all the subsequent choices. In contrast, something like utilitarianism can feel unwieldy — running a math equation with many unknown variables each time you have to make a decision. (But note, there’s no reason that truth tracks what is easy for us!)

Intensity

"The weight of unintelligible Rome might lie easily on bright nymphs to whom it was a background for picnics; but Dorothea had no such defence against deep impressions."

- Narrator on Dorothea, Chapter 42

By intensity, I mean those rare moments of true feeling. Much of life happens in half-color or half-sleep, with very rare and precious moments of something brighter and more essential. These are not always joyful — one feels intensity when in a physical fight or having a near death experience, but also when falling in love, stepping inside a cathedral, hearing a symphony play Wagner, holding a baby, contemplating the grand canyon, and the like. Intensity means allowing oneself to be moved: Dorothea recounts, “When we were coming home from Lausanne my uncle took us to hear the great organ at Freiberg, and it made me sob.” Her uncle comments to her husband: “That kind of thing is not healthy, … you must teach my niece to take things more quietly” (Chapter 7)

Intensity might be an aesthetic preference, but it can occasionally feel morally appropriate as well. That people still die of preventable diseases? That so much is ugly when it could be beautiful? There are problems where a staid response seems out of proportion, where intensity is the only morally appropriate one. Dorothea exhibits this intense emotional response to suffering: “A young lady of some birth and fortune, who knelt suddenly down on a brick floor by the side of a sick laborer and prayed fervidly as if she thought herself living in the time of the Apostles” (Chapter 1). To her, this is the correct response, to others it is extravagant and anachronistic.

But is it good?

“She did not want to deck herself with knowledge—to wear it loose from the nerves and blood that fed her action… But something she yearned for by which her life might be filled with action at once rational and ardent; and since the time was gone by for guiding visions and spiritual directors, since prayer heightened yearning but not instruction, what lamp was there but knowledge?” - Middlemarch, Chapter 9

I respect those who live their lives with altruism, consistency, and intensity. I admire this way of living. But as shown in the opening vignettes, this approach can lead to a wide range of outcomes, not all of which I agree with or think are good for the world.

I met someone recently who frightened me. They seemed smart, vigorous, intense, and ideological. We happen to believe fairly different things about the world, and we sit far apart on the political spectrum. I do not know which of us is more right, and which of us will produce better outcomes for the world.

On politics, someone once told me that the extreme left to extreme right pipeline, or vice versa, made more sense than you would think. What sets those people apart from others is that they care a lot about politics in the first place. It isn’t necessarily the content of those beliefs, it’s that they have them. They are already much closer to their seemingly opposite camp by virtue of being intense and ideological in the first place.

When I stared down this seemingly frightening other, I felt a shadow of that. We were the same. We were both aiming for that other directed, consistent, and intense way of being. We seemed superficially far apart, but we shared that hunger for an overarching set of principles, to know what is good and to do it, to take that question — and the provisional answers — truly, deeply seriously.

Dorothea said: "That by desiring what is perfectly good, even when we don't quite know what it is and cannot do what we would, we are part of the divine power against evil—widening the skirts of light and making the struggle with darkness narrower."

Let us hope that this desiring counts for something.

Thanks for sharing! Will definitely take a look at Middlemarch!

They say 'the road to hell is paved with good intentions', and I would agree that a lot of harm is caused by people convinced they are doing good. I therefore am afraid of letting this 'desiring' count for too much?

How do you see this? Doesn't this set the bar quite low? How can we keep our views in check and remain open to different ones?

And how do we also remain pragmatic in our daily altruistic actions without questioning them all the time, because indeed our intuitions could generally be right ?T